Enough water for everyone?

Some areas of Europe have only recently begun to think about addressing droughts and precarious water supplies. Elsewhere, people have faced water shortages for a very long time, and global warming is now exacerbating the situation. In the Andes, for example, strategies to supply people, animals and fields with water even during long periods of drought have a tradition dating back thousands of years. In view of acute water shortage, people in Peru today also resort to such old techniques: Pre-Columbian irrigation canals, called amunas, are being repaired and updated there.

"Reactivating historical practices and techniques can provide those affected with vital resources. But merely focussing on technology will not help us really understand how such indigenous infrastructures functioned. To fundamentally understand them, we need to look at the interaction between immaterial and material factors. Water plays a central role in prehispanic cultures where it links and interacts with spiritual symbolism, cosmological ideas as well as social norms and practices".

Kirsten Mahlke, professor of cultural theory and methodology

Water: common good and duty

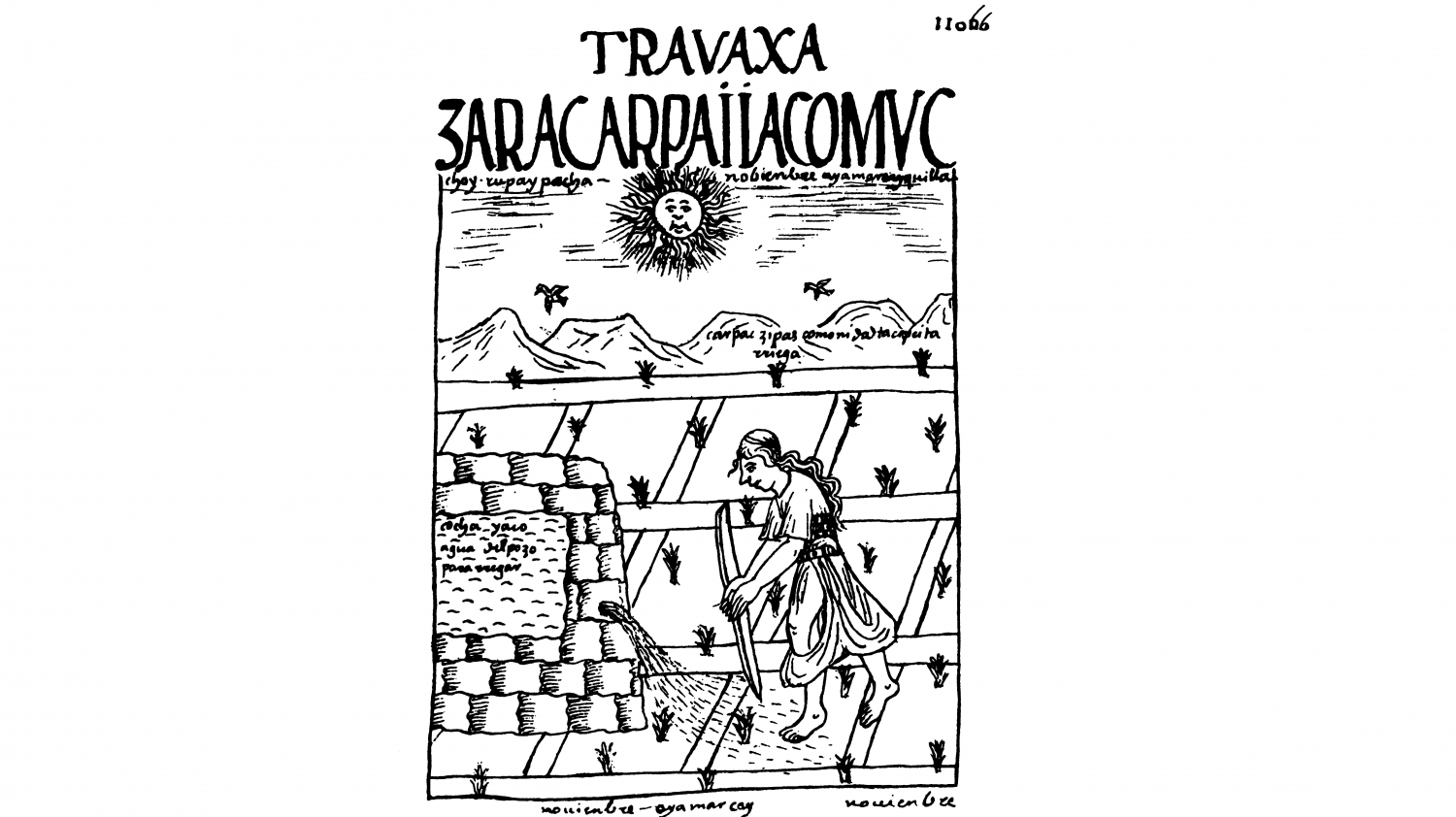

Mahlke traces these indigenous infrastructures in the colonial-era text "First New Chronicle and Good Government" by Guaman Poma de Ayala (Lima, 1615). The Andean scholar Poma laments that traditional water infrastructures have been destroyed by colonization and calls on the Spanish king to reform the colonial government so that it will provide for the needs of everyone. In his chronicle, Guaman Poma describes not only the nature of the irrigation canals and catch basins, but also the cultural dimensions in which they were embedded, such as myths, rites and laws. The Inca calendar was based on the cycles of water management, which were characterized by the alternating rainy and dry seasons. These cycles were also reflected in people's cosmological conceptions, in which the Milky Way appears as a "river" from which a lama drinks.

Illustration from the chronicle of Guaman Poma de Ayala, described as: "Young woman watering community bed, well water for watering, November"

source: Abb. 1 Royal Danish Library, GKS 2232 kvart: Guaman Poma, Nueva corónica y buen gobierno (c. 1615), S. 1162 [1172], URL digital facsimile: https://poma.kb.dk/permalink/2006/poma/1172/en/text/?open=idm747, last checked on 17.08.2023

According to Andean customary law, which dates back to before the time of Inca rule, water and land use rights were handed down only together. Water and underlying infrastructure were common property, with the municipalities being responsible for it. Cleaning, maintenance and repairs were performed autonomously by household communities (ayllús) in a kind of decentralized common good economy. "Guaman Poma describes the construction and maintenance of water infrastructures as a prehistoric mega-project of the entire Andean population that transcends administrative management and private property", Mahlke explains.

"According to Poma, the primary role of Inca rulers as well as the Spanish king is to act as guardians of a complex infrastructure that countless people built long ago and have maintained ever since. The strict laws of Andean water management were intended to ensure that everyone, especially the poorest, had water for their fields and animals".

Kirsten Mahlke

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire had disastrous consequences for the water supply as well. For their vast estates, called encomiendas, colonial rulers diverted water from the system, ignoring municipal water rights, maintenance obligations and seasonal rhythms. According to Guaman Poma, the Spaniards left little water for the indigenous population, forcing villagers to abandon their homes.

Holistic understanding of infrastructures

What can we learn by studying the cultural dimensions of infrastructure in this problematic situation during the colonial era? In the chronicle, the Spaniards' use of water infrastructure exemplifies a colonial system of ignorance and extractive practices. Destroying infrastructures is portrayed as a new type of crime that threatens past knowledge as well as present and future coexistence. According to Mahlke, the Andean alternative aims to withdraw infrastructure from the domain of individuals in order to enable the community to live a good life, regardless of the particular administration or form of government.

Irrigation canals were built under Inca rule (Tipón historic site, Peru)

Photo: Aga Khan (IT), Lizenz: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en , no changes

More than 400 years after the chronicle was written, the described conflicts over water supply continue to the present day, albeit with different actors. Today, for example, the indigenous Andean population is protesting against international corporations that are engaged in extremely water-intensive lithium mining in one of the driest areas of the world, thus threatening their livelihoods. "By studying infrastructures over long periods of time, the continuity between colonial and neocolonial economies emerges as a cultural pattern", Kirsten Mahlke states.

"The clash of such contrasting models of water supply systems as the Andean and the colonial Spanish ones cannot be understood without considering the social values and hierarchies, spiritual, symbolic and legal dimensions in which they are embedded. When it comes to managing droughts, such interwoven infrastructure knowledge is relevant today, and not just in Peru".

Kirsten Mahlke

Header Image: Water was not only essential for survival, but also had cultic significance (historic Inca site Tipón, Peru)

Photo: ESMERALDA118, Lizenz https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en, cropped