Mediterranean networks, Corsican clans and the transit point Marseille

One of the largest infrastructure projects of the 19th century was the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869. As a result, the Mediterranean Sea became a central passageway connecting Europe, Africa and Asia. How did this affect a Mediterranean island like Corsica?

Manuel Borutta: The Suez Canal globalized the Mediterranean Sea by connecting it to the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. The waterway then became the "highway of the British Empire", part of a key west-east shipping route between Britain and India. Many ports in the region were connected to Asia and eastern Africa as a result. Via Trieste, for example, the Habsburg Empire became a maritime empire. On the whole, the Suez Canal project awakened European fantasies of conquering new markets and territories in Africa and Asia.

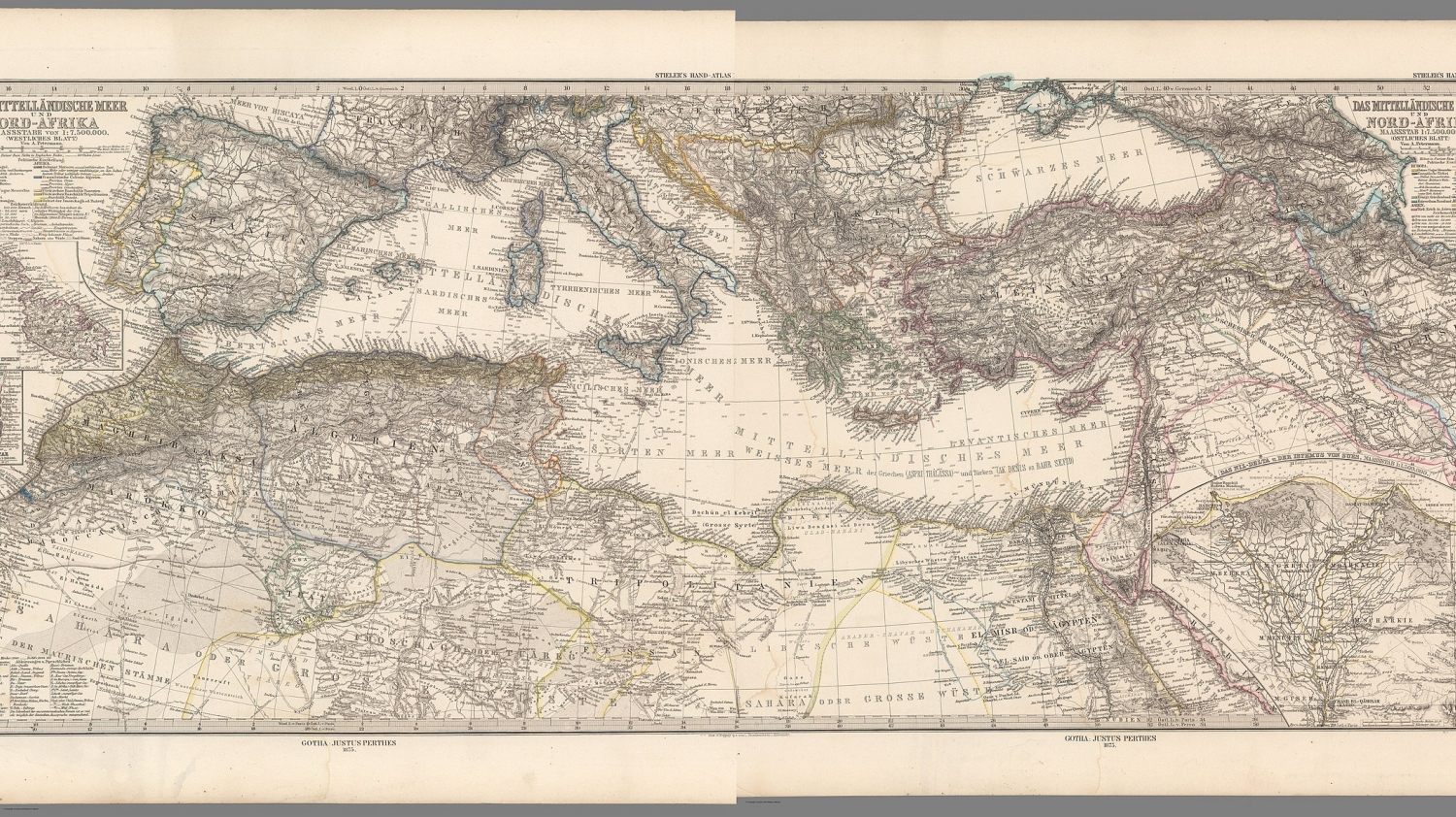

© https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~333114~90101275Map of the Mediterranean region from 1875, author: Adolf Stieler (1775 - 1836).

Yet, the project had less of an impact on Corsica since the island was not part of the global transportation and trade network. By contrast, there were dramatic consequences resulting from Corsica's connection to France's network of Mediterranean steamships. The island was flooded with industrially produced foods from the mainland, mostly from Marseille. This ruined the island's own agricultural industry and led to an exodus of its male youth. Thus, infrastructural connections can also have negative effects on society.

Since there was a lack of opportunities on the island, many young Corsicans emigrated to Marseille, Algeria or the French overseas colonies. Wherever they landed, Corsican networks sprouted and created what you refer to as "cultural infrastructures" in your article "Canals & Clans: Mediterranean Infrastructures". What do these cultural infrastructures look like?

Corsicans formed a cultural infrastructure of France's overseas empire: They were greatly overrepresented in the military, administration and police forces. At the same time, the colonial diaspora remained closely connected to the island of Corsica. They rarely mixed with other French people, but instead organized themselves, e.g. by setting up associations that represented Corsican interests in large cities and colonies, cultivated Corsican traditions such as language and culinary skills, and maintained ties to the island.

Manuel Borutta

In the 1950s, about 100,000 Corsicans lived in Algeria. One key goal of the organization "Corsicans of Algiers" was to expand the island's connections to the French mainland and its colonies. At the same time, Corsicans exported their cultural practices to the colony.

How exactly did this happen?

In 1878, for example, the united Catholic Corsicans of Greek origin from Cargèse moved their entire families to Sidi Mérouane and reconstructed their home village there: the language, symbols and rituals. They rarely mixed with other French people, but used the material resources of the colonial state, in this case the land taken from Muslims, and allotted it to members of their own families or clans. However, they hardly ever established colonies in the sense of the French administration of Algeria, but soon leased or sold the land back to the local people.

They thus used the empire's resources and channels for their own purposes. Corsican networks on the French mainland, on the island of Corsica as well as in Algeria played a crucial role in the fall of the Fourth French Republic in 1958. Such subversive usages of national and imperial infrastructures are what I would like to study more closely in the context of the cultural dimensions of infrastructures, one of our university's research priorities.

How did these Corsican networks develop in Marseille?

In early modern times, Marseille had been a destination for emigrating Corsicans. After 1900, the Panier district at the old port became a Corsican village. In the 1930s, Simon Sabiani, a right-wing populist politician with Corsican roots, rose to become a central figure in local politics as vice mayor. The power base for this "Mussolini of Marseille" was not only comprised of the Corsicans in the city whom he provided with work and homes, but also mobsters such as Paul Carbone, who also hailed from Corsica, and the Italian François Spirito, who used violence to intimidate Sabiani's political opponents.

© Édouard Baldus, CC0, via Wikimedia CommonsThe harbour of Marseille, around 1860.

In exchange, these gangs were given access to the prefecture, where they positioned henchmen to protect themselves from police prosecution and to control the new port of Marseille so they could export prostitutes to Latin America and import opium from Asia and the eastern Mediterranean to be processed into heroin in Marseille. This was the precursor of the French Connection that dominated the North American heroin market after the Second World War and was led by another clan of Marseille Corsicans, the Guérini brothers, who cooperated with the then ruling socialists. When Carbone was prosecuted, Sabiani publicly declared him to be a "friend".

That sounds like one hand washing the other or even cronyism!?

In this case a Mediterranean concept of friendship was used to declare the gangster Carbone to be a "man of honour" and to assert his innocence. Carbone and Spirito cooperated with Fascist Italy and Francoist Spain as well as with the German occupiers. Cultural networks and concepts were thus used to gain political power and organize crime on a global scale. The control of material infrastructures (the new port of Marseille) as well as Carbone's friendly connections to Corsican sailors from ocean liners who worked as smugglers played a key role. Intangible and physical infrastructures complement each other.

What impact did this cultural infrastructure have on the development of Marseille, and what were the historical consequences?

Between the two World Wars, the image of Marseille changed. The city came to be known as a type of "French Chicago". Due to the global connections of the new port and the goods, people and ideas circulating there, the regional port city became a Mediterranean metropolis as well as the de facto centre of the French colonial empire. Yet, it was also seen as a pit of globalization caused by unchecked immigration and violence, drug use and prostitution, political corruption and organized crime.

As a historian, which advantages do you see, not just in studying physical infrastructures such as canals, transportation routes and trading companies, but also in examining intangible infrastructures such as social practices?

I am interested in the interactions between both forms of infrastructure. Physical infrastructures, in this case canals, steamships and ports, can trigger cultural transformations: processes involving immigration, segregation and mixing as well as the abuse of political power and changes in representation. At the same time, cultural practices and networks can use these physical infrastructures for their own purposes as well as in other ways than those intended by the original architects of these infrastructures.

Manuel Borutta

Corsica is just one of many potential examples provided by modern history in the Mediterranean region. It would also be interesting to study Muslim pilgrims who used the steamships and railroads of European companies to travel to Mecca and who became Islamic fundamentalists or Arab nationalists along the way.

Marseille is still considered one of France's trouble spots with extreme levels of drug-related crime, which the government seems unable to bring under control. How could a better understanding of cultural infrastructures contribute to positive changes?

First of all, we should not use the term in a normative way, but keep it neutral so that it can be made analytically fruitful. As I indicated, there is by no means a lack of cultural infrastructure, for example, in the area of organized crime. So far, the French state has not succeeded in penetrating the neglected quartiers nord along with the area's cultural infrastructures. Instead, the state has partly withdrawn from this area and left its inhabitants to their own devices and the drug lords, who, for example, set up inflatable swimming pools in the summer, since there are not enough public pools for the many families who cannot afford to travel on vacation. In this case, organized crime takes on the responsibilities of the state, keeps order in the district and allocates resources. It will not be easy for the state to win back these areas because of a lack of trust and non-violent communication. Positions for neighbourhood contact officers were eliminated in 2003 when Nicolas Sarkozy was Minister of the Interior. Since then, parts of the quartiers nord like the blocks of the cité de la Castellane, where Zinédine Zidane was born, have become police-free zones. They are now controlled by heavily armed gangs.

France's current President Macron has launched a five-billion euro plan for Marseille: "Marseille en grand". The prerequisite for receiving this massive state support was that neglected quartiers, especially in the north of the city, would get better connections to the already partially gentrified city centre. This is a step that, for decades, local politicians avoided taking. In the meantime, the first streetcar lines have been installed. It will be very interesting to see how this urban intervention affects the city and who will ultimately come out on top in the fight for Marseille. The field of cultural inquiry cannot solve these complex social, economic and political problems. However, infrastructure research involving the fields of anthropology, sociology, history and literary studies can contribute to a better understanding of these conflicts and dynamics. For this, we need a theoretical foundation for the concept of cultural infrastructures, which is a focus of our university's corresponding research priority.

Manuel Borutta is a professor of modern and contemporary history at the University of Konstanz who specializes in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Since 2018, Manuel Borutta has been coordinating the research network "The Modern Mediterranean: Dynamics of a World Region 1800-2000" funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). He is currently writing a book on the Mediterranean entanglement between Algeria and France in the (post-)colonial age and is making preparations for an "Oxford Handbook of the Modern Mediterranean" (to be published with Oxford University Press).

His article "Canals & Clans: Mediterranean Infrastructures" was published at the end of October 2023 in the book "Rethinking Infrastructure Across the Humanities" (editors: Nora Binder, Fernando Esposito, Aaron Pinnix and Axel Volmar) by the Transkript Verlag publishing house. The book is available online free of charge (open access).

Header image: The new port la Joliette as well as pont transbordeur above the old port were iconic for Marseille's modern infrastructure. Copyright: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain.