Eating together in humans and bonobos

Food plays a major role in our world. We celebrate by eating food together. We enjoy good food. And we cook for other people to do something good for them. Eating together also plays a central role in the animal world. In their research, researchers Barbara Fruth and Britta Renner from the Cluster of Excellence Collective Behaviour at the University of Konstanz are investigating how humans and bonobos (great apes) eat and what food intake has to do with social behaviour. They report on their research findings in the podcast "Exzellent erklärt" - a joint podcast project of the 57 Clusters of Excellence that are funded as part of the Excellence Strategy of the German federal and state governments.

Eating together creates a shared social identity

"When we deal with nutrition in our society, we always look at what happens to the food 'after the mouth'. Does it make us ill, is it good for us? How does it affect our biology and physiology?" says Britta Renner, spokesperson for the Cluster of Excellence Collective Behaviour. However, the Professor of Health Psychology at the University of Konstanz and her research group are looking at what happens "before the mouth", i.e. the social processes at the table.

"When we place shared food in the centre and eat from a shared plate, we see positive effects on social identity: we actually feel closer to each other afterwards."

Britta Renner, summarising the research results to date

While humans enjoy sharing food, this is rarely the case with bonobos, as Barbara Fruth, group leader at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, has observed. She says: "As a rule, the giving of food follows certain traditions. Certain begging behaviour is expected. Then food can be given or taken. It is also very rare for bonobos to give food voluntarily." The behavioural biologist heads the LuiKotale Bonobo Project and has been working with bonobos in the wild for over 30 years. She has not yet observed them being invited to eat. But there is another exciting phenomenon among the great apes, as Fruth explains: "Children are always allowed to take food, regardless of whether they are related or not. That's great to observe."

How collective behaviour is researched: From observation with binoculars to labs with Hollywood-style equipment

But how do you research people and bonobos eating? Barbara Fruth has been travelling to the central Congo Basin, the region where bonobos are native, for over 30 years. Over several years, she has acclimatized two communities of 100 individuals to the presence of the researchers. It is now possible to observe the animal groups while taking many ethical aspects into account - the researchers mainly work in the traditional way with binoculars and questionnaires.

© Christian Ziegler, Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior

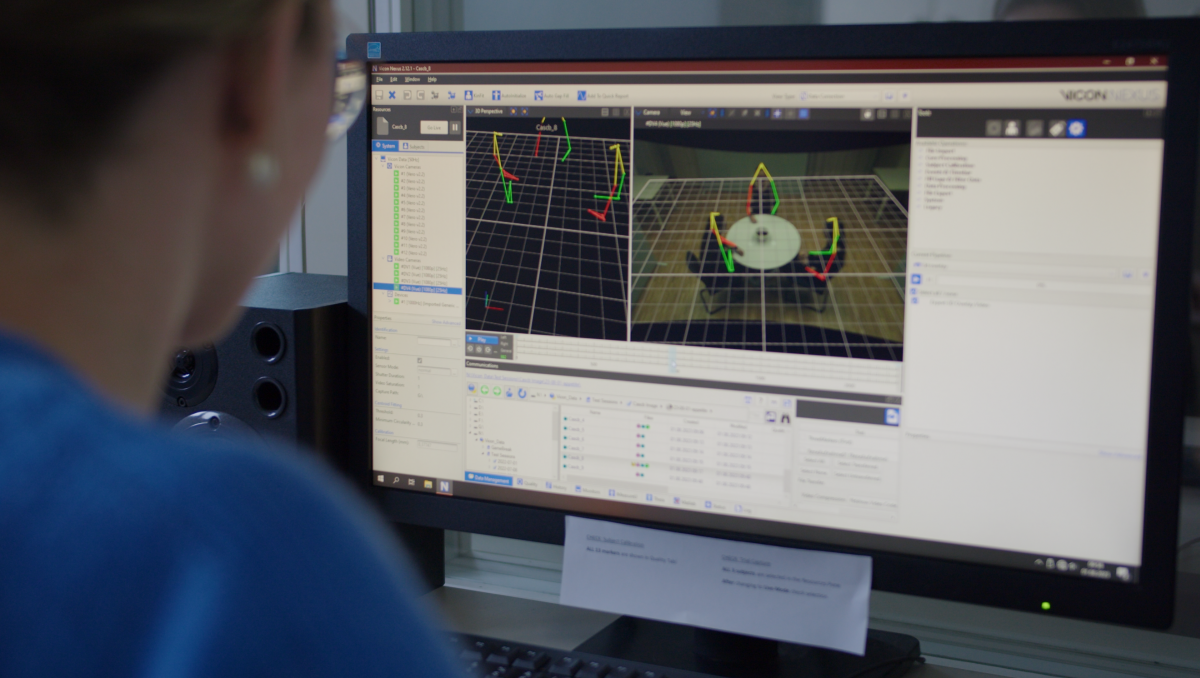

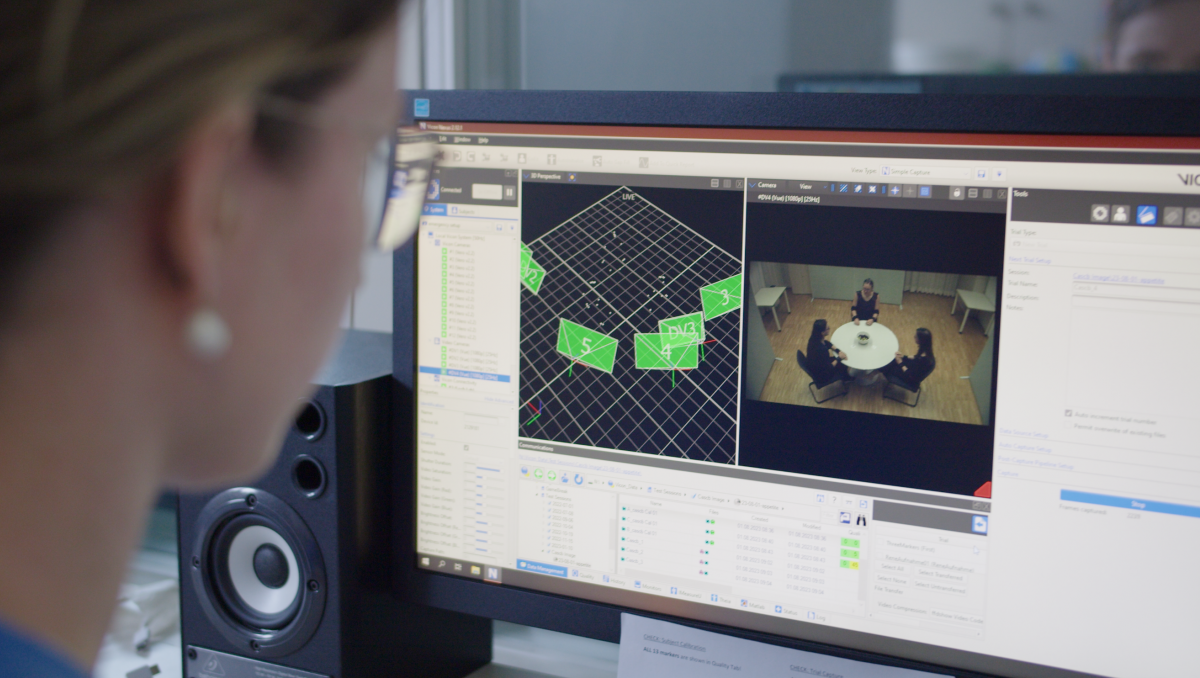

However, the situation is different when researching people's eating behaviour. Britta Renner invites study participants into her laboratory: Thanks to motion-capture cameras and microphones, her team can study how people behave while eating. "You would think that the people are biased. But that goes away very quickly. Especially because we don't usually analyze people individually, but as a group," says Renner.

But it is not only the relevance of collective eating that is being researched at the Cluster of Excellence Collective Behaviour. The scientists are also focusing on swarm behaviour and intelligence in general: "I don't think there's anyone who isn't immediately fascinated when they see a school of fish or birds moving elegantly," says Cluster spokesperson Britta Renner.

"In my opinion, collective behaviour is a phenomenon that is central to the pressing issues of our time - from climate change to mobility behaviour and collective appetite."

Birtta Renner

You can find out more about the research into collective behaviour and the similarities and differences in eating between humans and bonobos in the podcast Exzellent Erklärt, episode 41 (in German)

Headerimage: Bonobos share an Annona fruit