Waggle dance mysteries

As summer ends, it marks the time of year when bees need to store enough food to survive the winter. Then it is also high season for the bee researchers led by James Foster, a neurobiologist and group leader at the Cluster of Excellence Collective Behaviour at the University of Konstanz. Day in and day out, whenever there is good weather, the team sit on campus, observing with focused attention the bees from their research swarm as they fly to a feeder with sugar water. They record the colour and number of each bee, which they previously marked with tiny stickers. But what exactly are they researching? And how do they go about it?

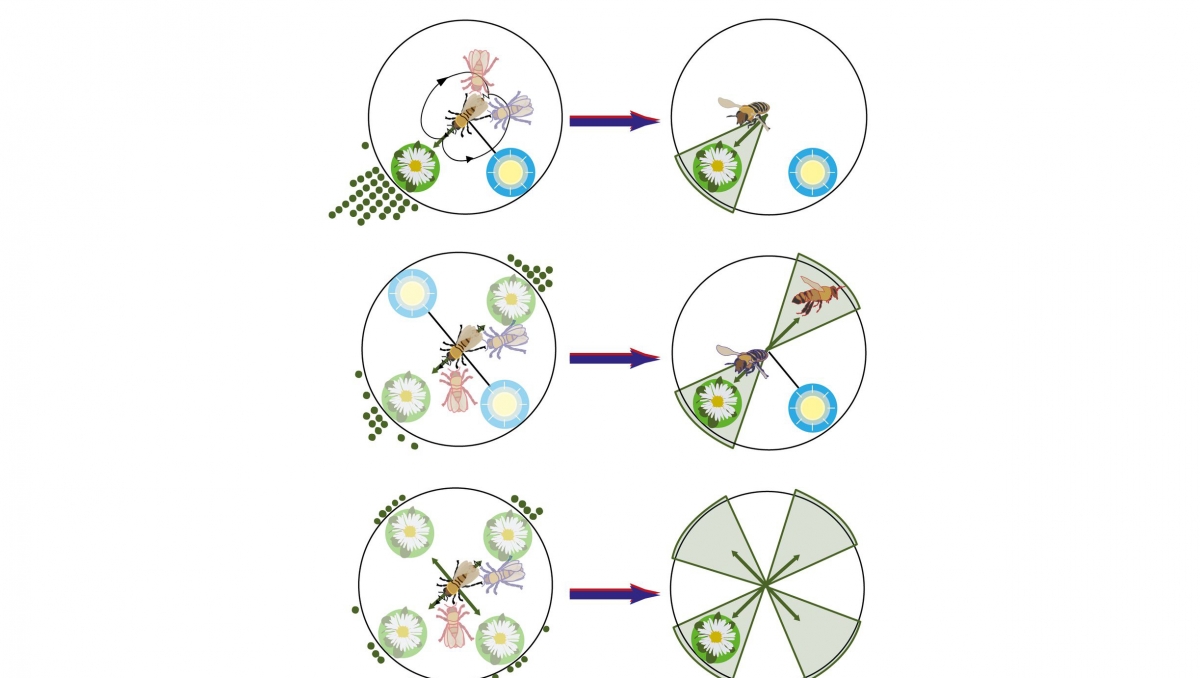

“In our experiments, we are focusing on the waggle-dance followers, so we are aiming to catch them wherever they fly to,” explains James Foster. After decades of careful experiments, it is very clear that the followers are good at interpreting dances to determine the location that the dancer wants to communicate.

“We are now trying to find out what the followers do when the dancer cannot communicate perfectly. What if the dancer is imprecise when she dances? What if she herself is not quite sure if she flew North or South from the flower? One thing is certain: in either case, it certainly does not stop her from dancing.”

Neurobiologist James Foster

What do the followers when the dancer cannot communicate perfectly?

To answer this, Foster and his research group manipulate dancers returning from a new feeder so that her dance becomes imprecise or even ambiguous. Frida Hildebrandt, a doctoral student at the Cluster of Excellence Collective Behaviour, explains this further at their custom-made research beehive. This hive is located in a well-darkened room at the University of Konstanz. She pulls back a black, light-blocking curtain. Now, the beehive can be seen through a glass pane. “Bees always dance on a vertical surface – the honeycombs of wild bees in nature are always arranged vertically. For the bees, ‘up’ represents the sun”, explains Frida Hildebrandt.

Over the next few weeks of experiments, the plan is to occasionally tilt the frame with the honeycombs, which was specially built by the University of Konstanz's scientific engineering services, across a range of angles from a few degrees to completely horizontal. Then Frida Hildebrandt points to a camera, “We record the dances with this camera in night shot mode since the honey bees dance in the dark. Through the recordings, we can later analyze what information the bee provided and how it changed depending on the position of the frame.”

© Elisabeth BökerFrida Hildebrandt observes the beehive.

Who makes it to the feeder?

Today, it’s the bee with the red number 91 that Frida Hildebrandt observes dancing. She almost expected it, having seen it several times at the food source outside beforehand. Five bees are following the dance. Frida Hildebrandt notes their numbers and informs her two colleagues outside which bees they should keep an eye on.

James Foster and his student assistants are now curious to see whether and which of the five insects arrive first at the feeder. “This tells us how they interpreted the dance and whether they were able to work out what the dancer was trying to tell them,” says Foster. But this requires a lot of patience right now during the experimental season. After 15 minutes, the first bee arrives – it is white 26. The only one of the five in today’s experimental session. After the experimental season the team will work on the data and try to determine why the four others were not finding the food source.

Elisabeth Böker

Verwandte Artikel: