Looking into emptiness

It all started with an interest in temporality. Calendars from the 17th century aroused the curiosity of early modern historian Achim Landwehr. As cheap mass media, they were sold by the millions back then. Every household had such a calendar, but it looked very different from today: Calendars were packed with information, predicting what would happen during the year, touching on the weather or planetary constellations, and also including tips on when to cut hair or harvest crops. Landwehr was rather surprised when he noticed that the calendars in the second half of the 17th century were quite empty, with nothing left but the date. Why?

The researcher explains: "I thought that there could be a story behind this banal media development. That it might demonstrate a different attitude about time, a different approach to time, and, thus, to the world. If you no longer think that everything is predestined in the divine plan of creation, time is suddenly no longer predeterminable. This means that you can manage time yourself. These empty calendars invite you to fill them."

Page from a calendar with space for notes printed in Munich in 1716.

Page from a calendar with space for notes printed in Munich in 1716.

An omnipresent phenomenon

The fascinating thing about temporal gaps: They affect every individual as well as society as a whole, every era, local events and the universe. People do not yet know, or no longer know anything about the largest part of time that concerns them.

"Although we have no access to these absent times, we don't just exist in the here and now, but we exist and work with past and future times, too. So we are constantly working with empty spaces, and filling in the calendar pages. However, we know that some of these pages will remain permanently empty. We cannot reconstruct the past one-to-one. And despite all the modern forecasting possibilities, we are aware of their limitations."

Achim Landwehr, Chair of Early Modern History at the University of Konstanz

Whether in politics, science, technology or business, the more Landwehr searches for the phenomenon of voids, the more he finds. It's the famous bottomless pit. Since he cannot cover all historical periods, Landwehr concentrates on examples from the early modern period, i.e. the 16th to 18th centuries. He is particularly interested in the role that voids play in modern societies – in a phase of world history that is increasingly dominated by European-Western cultures.

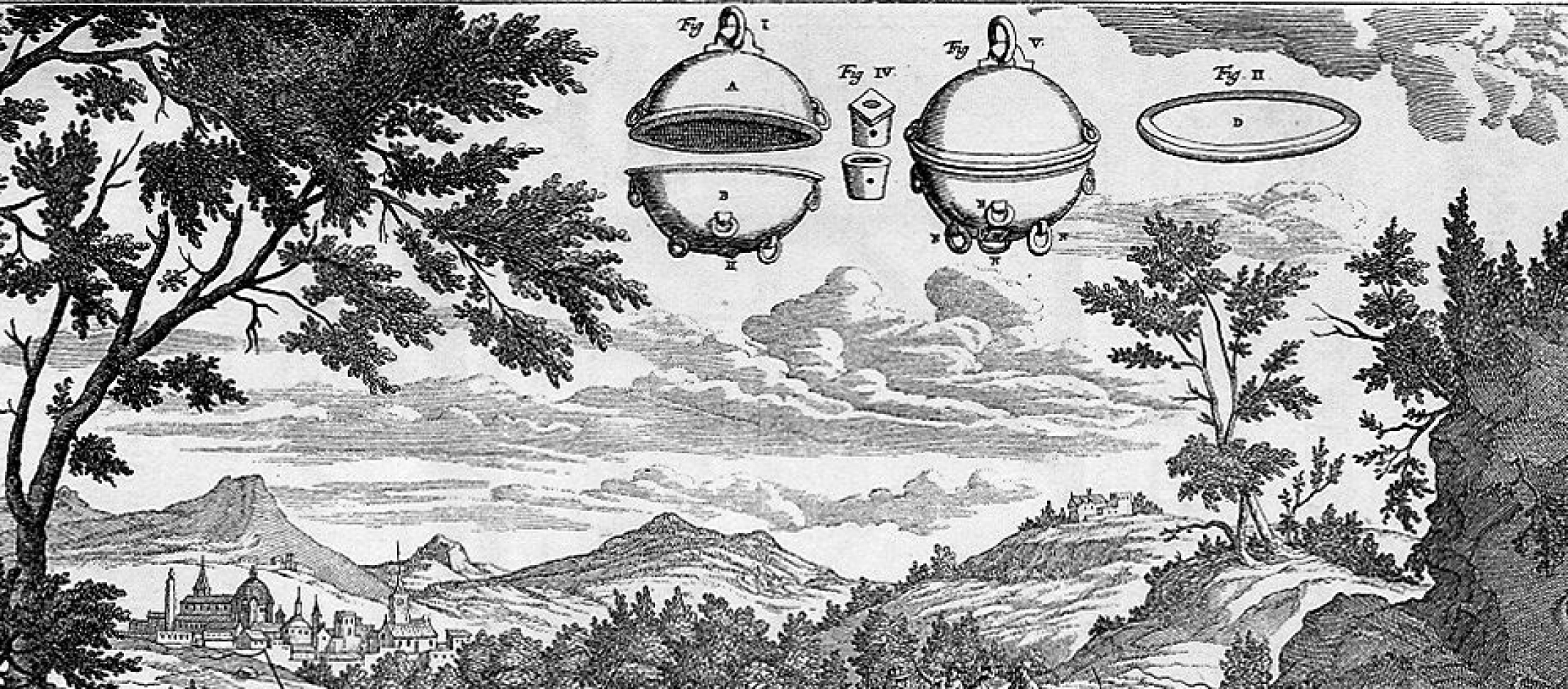

Around the same time as the calendars start to become more empty, the discussion about the vacuum arises. Previously non-existent in the European debate, it suddenly became conceivable that there was such a thing as empty space, according to Landwehr. Within twenty years, from the 1640s to the 1660s, several researchers across Europe – Otto von Guericke in Magdeburg, for example, and Blaise Pascal in Paris – demonstrated this empty space by means of experiments. "And that has a massive impact", explains the historian. "Because suddenly everything that had been considered right and true over 2000 years of Western tradition is no longer true. The Aristotelian way of thinking – that nature abhors emptiness – was continued in the Christian era. This emptiness triggers a crisis on the one hand, but on the other, it opens up new possibilities.

How do gaps and emptiness come about?

How well can we recall the last 24 hours? And how much more difficult does it get when it comes to the last 10, 100 or 500 years? According to Landwehr, gaps are the norm for times that are no longer immediately available to us. Forgetting, loss and the omission of historical events are all unavoidable. "What is left is not the tip of the iceberg, but rather a small dome of snow on top of the iceberg", the historian says.

However, gaps can also be deliberately created, especially when it comes to images of the past and historical narratives.

"How long was it possible in Germany to gloss over twelve years of National Socialism in a company's history with a half-sentence? This way of producing memory gaps is a well-known and recurring phenomenon."

Achim Landwehr

Such empty spaces were deliberately created in the early modern era, too, for example when European colonial powers encountered indigenous peoples. The latter were said to have no history of their own, which served not only to postulate the colonialists' "superiority" over the indigenous peoples, but also to deny these peoples the legal title to the land on which they lived. This same strategy was employed even more intensely in Africa in the 19th century.

A laboratory of modernity

Landwehr finds the 17th century particularly interesting because many of the challenges and contradictions that characterize our modern life can be observed in that period as if in a laboratory situation. An example: With the Little Ice Age, the 17th century was also confronted with the opposite climate crisis as today.

Between 1570 and 1720, the temperature across Europe fell by an average of around 1.5 degrees. The intensity of the solar radiation decreased due to a change in the sunspots. Multiple crop failures led to famines. People feared the end of the world. The search for culprits led to the "witch hunts", which peaked at the same time as the Little Ice Age.

People noticed the cooling climate and wondered: What is happening right now? What does this mean for us? Questions about the meaningfulness or meaninglessness of one's own actions were raised, as well as the question of what the future might look like. "The answers to the Little Ice Age were completely different from those to the current climate crisis", explains Landwehr, "because they were sought on a religious level. They followed the lines of: 'God wants to punish us with what is happening because we have done something wrong. So we have to try to bring the system back into order'."

The Little Ice Age brought snow and ice to the Netherlands, as art testifies to this day.

The largest void of the 17th century

The insecurity triggered by the Little Ice Age initiated a process that must be seen as extremely fundamental, according to Landwehr:

"This is probably the biggest void that emerged in that period: That a world model that had been uncontested for a good one and a half millennia, namely the religious world model shaped by Christianity, was gradually beginning to crumble."

Achim Landwehr

The first explicitly atheistic discussions were held from the late 17th century onwards. The idea that God simply might not exist was so outrageous and radical that it had a world-shaking effect. At the same time, other scientific models emerged to explain the natural world.

The historian therefore sees the parallels between the 17th century and the present day not in the question of responsibility, but in the psychology of a situation in which seemingly reliable foundations "simply disappear". Like today's belief in progress, unlimited growth and a future with open possibilities. "In both cases, the constellation of problems is one in which previous answers no longer work and people have to search for new answers and methods – only that they did not know exactly how, just like we do not know today", explains Landwehr.

© Poul la Cour & Jacob Appel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons / https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Magdeburg_hemispheres.jpgThe Magdeburg hemispheres were part of Otto von Guericke's scientific experiments. Like Torricelli and Pascal shortly before him, Guericke proved the existence of the vacuum.

Goodbye to the progress model

"Unlike back then, today there is no longer a clear answer to this search for meaning", says the historian. "In the current polycrisis, there is no longer any clear answer to the question of how the existence of humans on this planet can still be meaningful". Landwehr describes this as a void, too, a cultural and also a historical void: In the field of history, a chronological model of growth and progress is still used. If you get the chronology right – so the idea – history will continue in the same way.

The historian disagrees: "That no longer works today. It is no longer just about voids as a theme, but also about gaps in history's ability to continue to tell the story of the human era. I don't have an answer either, just yet. But that's what science is all about: looking into questions you can't answer yet".