The tinkering mindset

"Everything is a prototype. Nothing is ever truly perfect".

Robert Pazdzior

Its only about fifty steps, just a few metres that separate the FabLab from the chemistry building at the University of Konstanz. Robert Pazdzior knows the way, as he has taken these fifty steps frequently, practically every day. Back and forth, then back again. Every trip to the FabLab brings him a bit closer to his goal of building his own automated system for studying and optimizing chemical reactions. He is building a completely new system to fit the specific requirements of his research team, the solid state chemistry group previously led by Professor Miriam Unterlass.

Pazdzior is not an engineer. He has a doctorate in biochemistry and molecular biology – not exactly the type of background you expect for someone building technical systems. "I have always had a tinkering mindset", Pazdzior explains how he got started. And truly, a perfect constellation emerged: On the one hand, there is the committed autodidact with a wrench in his hand. On the other, the University of Konstanz's FabLab that provides an open workshop for those, like Pazdzior, who love to make and to tinker. The workshop was an excellent match for his inventive nature and gave him a place to put his creativity into action and build a machine to conduct cutting-edge research.

© Jürgen GrafMeeting in the FabLab: Robert Pazdzior and FabLab manager Manuel Bernhardt.

But wait a minute!

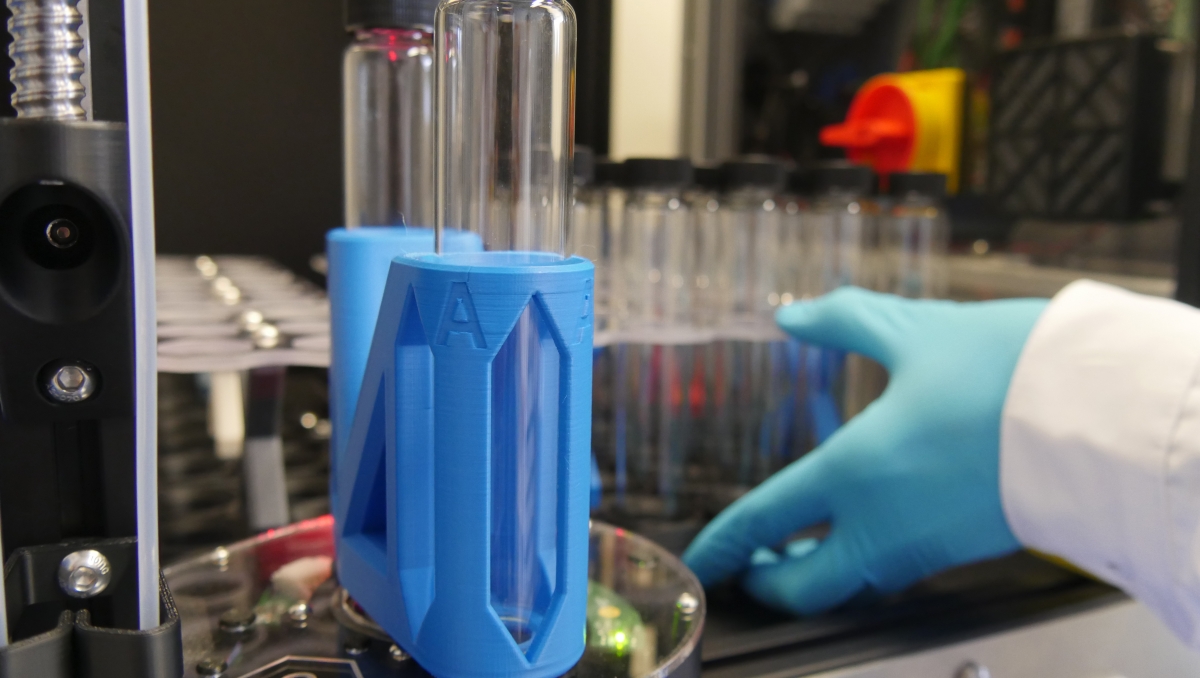

What on earth is the automated system even for? To understand why Pazdzior's project is so special, we need to start with the machine. Or we should actually start with the research team behind the project that studies how chemical reactions can be improved and made more sustainable through the clever choice of reaction conditions. Chemical synthesis can differ depending on factors like temperature, the pressure acting on the reagent, the solvent used – and many more. Choosing the right conditions is critical to getting the intended outcome from chemical synthesis – and can make reactions possible that had previously been unthinkable.

The only problem is that it takes time to test out different reaction conditions – a tremendous amount of time. Over and over again, researchers add reagents to a vessel, systematically tweaking the conditions, stepping the reaction temperature up or down, trying to optimize the reaction outcome. It can take hours, or even days, to test a particular set of conditions. It takes so much time that teams often only test the conditions that they deem to be the most promising – and generally don’t stray too far from the beaten path. However, this is not enough for the solid state chemistry research team in Konstanz. They want to discover new and exciting chemistries in the world of hydrothermal synthesis. Creativity stems from leaving the beaten path, and, for the most part, scientific breakthroughs come from uncharted territory.

This is where Pazdzior’s machine comes into play: If researchers don't have to spend hours preparing the reactions themselves, and can instead queue up a bunch of reactions and let the machine do the tedious work, then their hands and minds are free to explore avenues of research that they simply would not have had time for otherwise. A machine that can carry out a sequence of reactions doesn’t necessarily have to get its instructions from a human scientist either. This opens up the system to the promising world of AI and machine learning driven exploration.

This sounds great – so why not go online, order the machine and have it delivered right away? While commercial solutions exist for some isolated parts of the system, the exacting requirements for exploratory hydrothermal synthesis demanded a more bespoke solution.

"We started with a blank sheet of paper."

Robert Pazdzior

A plan emerges to build their own machine.

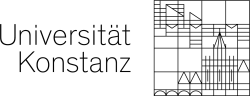

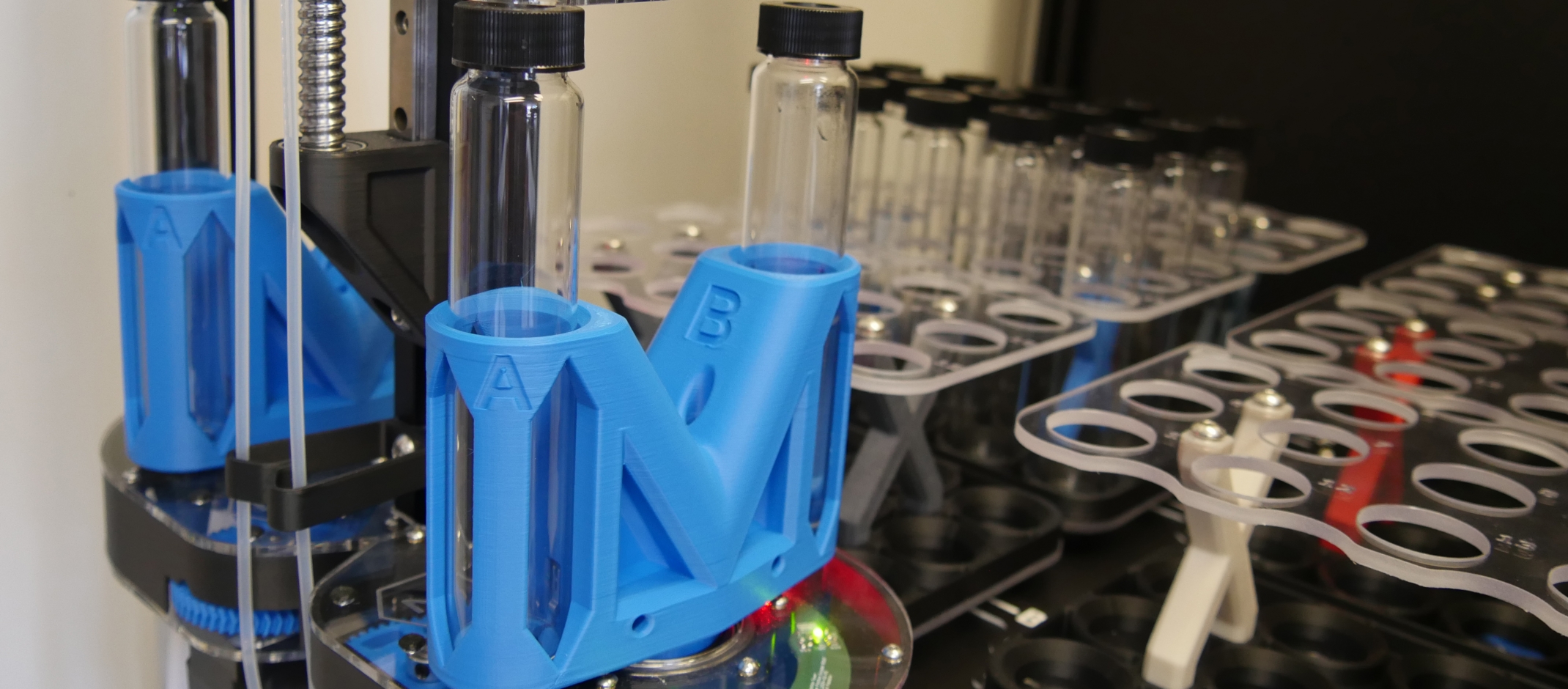

"We started with a blank sheet of paper", Robert Pazdzior explains. "At first, I had no idea what the reactor would even look like". He began by thinking about how the chemicals could be transported into the reactor – without knowing exactly what it would look like. After all, you must start somewhere. So, he began with the system for grasping and moving the large test tube-like sample vials. The first design iteration of this robotic hand was quite large, the second much smaller and with 3D-printed rubber-like "fingers". But finally, Pazdzior settled on a design with custom laser-cut appendages.

With the tube handling sorted out, he moved on to designing the injection station: a system for injecting multiple chemicals into the reactor through large syringe needles. The injection station also automatically cleans itself between reactions so that it can always start fresh.

Robert Pazdzior continued the work, step by step. He filled in each gap in the process, and bit by bit, his "blank sheet of paper", too.

Reworking the idea, again and again.

You never build just one final machine – but a countless number of prototypes. Robert Pazdzior can't say for sure how many versions of each little component he has designed, perhaps two or three at least, but he is certain of one thing: he could have gone on tinkering for ages. "Everything is a prototype", he likes to say, "Nothing is ever truly perfect. You can always tweak just one more thing". But along the way, he learned some important lessons about knowing when something is finally "good enough", and how to avoid getting lost in the minutia of a design.

A workshop for creative thinking

Robert Pazdzior started building the system as a one-man engineering team. But that changed when the FabLab came into the picture. The University of Konstanz's FabLab is an open laboratory that provides "tinkerers" with easy access to tools like 3D printers, laser cutters and much more. However, the FabLab workshop offers much more than just tools: It's also a place for creative thinking.

"The FabLab changed how I thought about the design and engineering process", Pazdzior says. Though he’d already built a 3D printer for rapid prototyping at this point, gaining direct access to new tools in the FabLab – especially laser cutting – opened up new avenues to design and prototyping. In addition to providing a new set of tools, the FabLab fostered exchange with like-minded people.

The FabLab was a game changer. Robert Pazdzior was now able to try out many new ideas very quickly and easily. Whenever the FabLab was open, he was there. "He often sneaked in when it wasn't actually open", the FabLab team jokes. Robert Pazdzior is always welcome there – as if he's part of the team. It was also at the FabLab that he met a key partner for his project: Thomas Schuchhardt, an electrical engineer from the university's Scientific Engineering Services.

© Jürgen GrafThe team behind the machine (from left to right): Hannah Mehringer (Solid State Chemistry working group), Thomas Schuchhardt (Scientific Workshops), Robert Pazdzior and Manuel Bernhardt (FabLab).

Once a week, Schuchhardt comes to the FabLab and answers questions, shares tips and tricks. "We have a partnership with the FabLab so that I can be on hand to advise people who bump up against their own limitations while working on a project", he explains. Schuchhardt and Pazdzior linked up fast. "Robert's project fascinated me. For someone without a background in engineering, the way he works is incredibly clean. We developed a really great partnership. My collaboration with him has grown closer and closer, and I have taken on parts of the project, especially those involving programming".

What began as an individual project has long since turned into a team effort. And it is the team that will finish the machine: As many young researchers do, Robert Pazdzior has moved to a new location: New York. He leaves behind a solid foundation for the automated system and passes the baton to his research group for the final steps.

And what's next for Pazdzior? In New York, he plans to build himself a new 3D printer and to continue working in automation, but perhaps a bit closer to his roots in biochemistry and biology. Whatever happens, we are sure that Robert Pazdzior will remain true to his tinkering mindset and will always have a project where he can tweak "just one more thing". Like he says: Everything is a prototype.