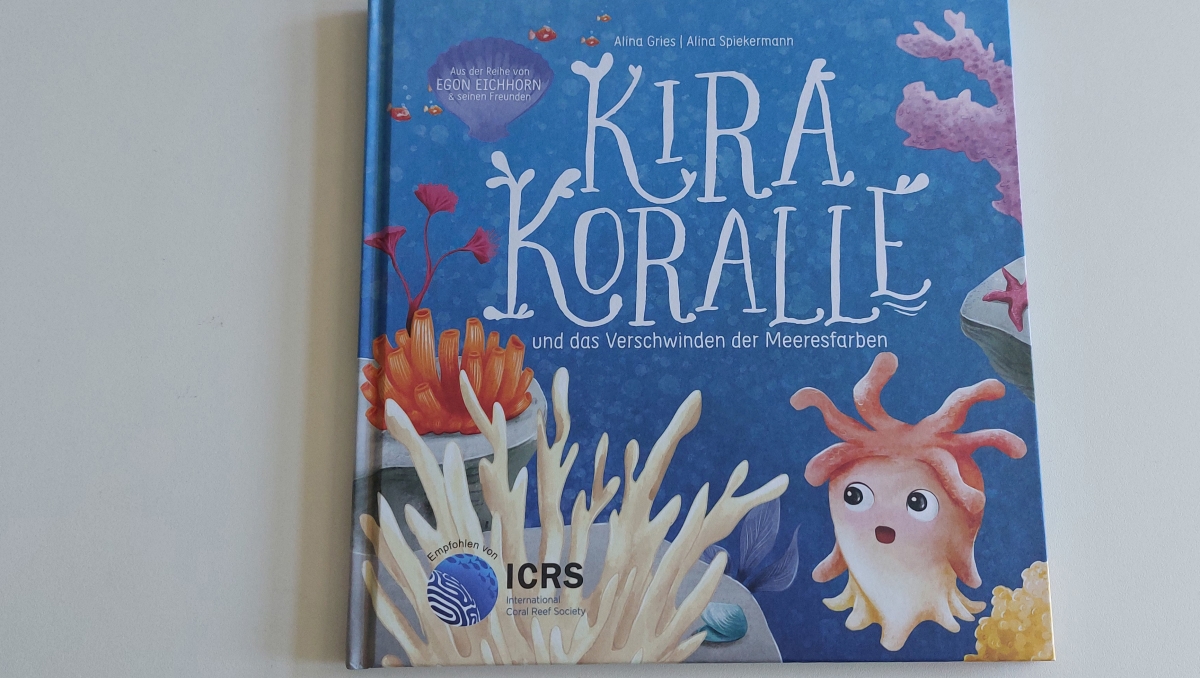

A little coral adventure

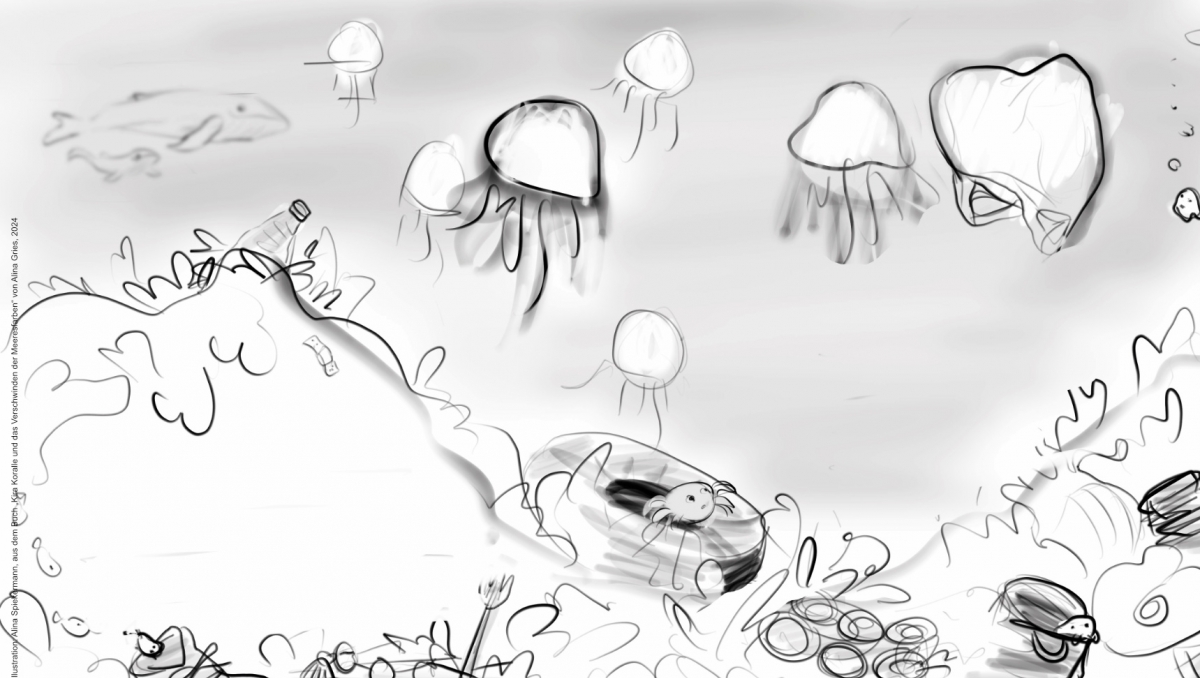

The little coral Kira swims through the vastness of the ocean. She is looking for algae that will help her shine in bright colours. But why are there so many pale corals in the sea? And what strange objects are floating everywhere in the water?

"I want to be the most colorful sea flower in the whole ocean."

Kira Koralle

What at first sounds like a funny story with lots of colourful pictures has a very serious background: Coral mortality continues to increase worldwide. A few weeks ago, it was confirmed that coral reefs are bleaching globally for the fourth time. Researcher Christian Voolstra from the University of Konstanz knows what far-reaching significance the death of these important marine organisms has for everything; corals build reef ecosystems, which provides a habitat for a myriad of species. He is particularly pleased that he could now pass on knowledge in the form of a children's book.

Mr Voolstra, the book "Kira Coral and the disappearing colors of the sea" was published in April. You were involved in its creation as a scientific expert. How did this come about?

Christian Voolstra: Alina Gries, the author of the book, had already written two children's books that dealt with environmental protection. For her third book, she had the topic of corals in mind and simply wrote me an email asking if I would support the process. We didn't know each other at the time and she was a bit surprised that I replied immediately. Apparently, that was not the usual response to such requests. Many scientists are rather reluctant to engage in public relations work. But I spent a long time abroad where things are a bit different and research and society are connected much closer. I think it's important to transfer more research findings to the public in Germany too – also in a simple form.

What happened then?

Alina sent me her other books first and I thought they were very good. They give children easy access to important environmental topics. I'm of the opinion that you can't and shouldn't keep everything negative away from children. They do not need to know every detail, but they are aware of what is happening around them anyway. It is important to explain certain things to them – for example, what consequences it has when we disregard nature. In this case, the bleaching of coral.

What is coral bleaching?

The phenomenon that has become all too well known as coral bleaching means that corals at the scale of entire reefs lose their colour. What seems like a visual flaw has devastating consequences: If the corals bleach, many of them die soon afterwards. That is a catastrophe for the oceans and for the Earth ecosystem.But what exactly happens? The corals' colour diversity is the result of their symbiosis with microalgae. By means of photosynthesis, they provide the corals with a large part of the energy they need. The colour is basically just a by-product, caused by the pigments that capture the light for photosynthesis.

However, the microalgae react very sensitively to temperature fluctuations and emit substances that cause the corals to react: they reject the algae, thus stopping the energy supply. What follows is initially a fading of the coral colour, and ultimately starvation and death – alone or in masses.

It seems you have experience working with children?

I have three children. My eldest daughter even contributed some ideas to the book's content and was a test reader. I have already presented my work at the children's university programme at the University of Konstanz and given presentations in schools. So, explaining scientific processes in a simplified way was not entirely new to me. But the development of a children's book was a first for me.

Did you come up with the story about Kira yourself?

No, the author Alina Gries did. After our first contact in August last year, we spoke a few times to set the scene. In early December, she sent me the first draft of her story, still quite abstract in tabular format. The accompanying illustrations were to be created later. That required a fair bit of imagination. On this basis, we discussed and revised the details. Sometimes it was just small linguistic subtleties, but sometimes the content was not quite correct. Which can happen quickly if you transfer known patterns to a new material. In the first version, Simon the sea urchin curled up in fright. We all know that this is what hedgehogs in the garden do. However, sea urchins do not curl up, they are rigid – but they can retract a little. This was then rewritten accordingly.

With Kira, it was mainly how she looked in the drawings. Kira is a coral with 6-fold symmetry. The tentacles are always six or a multiple of six. But in the first draft, Kira's "hairstyle" consisted of many tentacles, which was corrected correspondingly.

That sounds like a lot of work. How long did it take to write the book?

Surprisingly, not as long as you might think. Alina contacted me in August 2023. She sent the first draft of the story in November or December and we edited, moved things around and tweaked details until March. The first edition was published in April.

I was surprised how quickly and well everything worked. There were certainly some challenges. It wasn't so easy to find names for the characters, as many names are already protected by copyright – and then it had to sound good in English, too.

There is also an English version?

Yes, it was produced and released at the same time. I translated and edited the English version, which was almost more strenuous than writing a scientific paper. To be honest, I totally underestimated how much work it is to stay very precise and make sure the language remains consistent throughout the book.

In scientific publications, you can make changes right up to the last moment. And that is how I had planned my schedule. The author and the illustrator, however, were rather irritated when I came up with changes again and again, shortly before printing. They were aiming to have everything finished a month before.

Was that the biggest challenge?

Yes, I think so. At some point, I no longer wanted to proofread (laughs). Unlike in science, where the publication of a paper can be postponed if necessary, the book's printing date was fixed and there was no question of changing it. This is where I really had to focus.

Was everything that was important to you implemented in the end? Perhaps even something from your current research work?

Yes, the book now quite explicitly covers coral bleaching and climate change. That was not quite so clear at first, but on the final stretch I pushed to stress these issues. In the end, everything that was important to me was realized, and it was a really good collaboration with the author. My latest results would have been too specific. The book should outline the topic more generally.

Have you already budgeted your royalties from book sales?

(laughs) No, I decided not to take a penny. My biggest takeaway from the book is that I was able to establish a connection between the authors and the coral conservation programme SeaChange Indonesia, which we work closely with. Furthermore, the International Coral Reef Society (ICRS) officially recommends and financially supports the book. A coral is planted for every copy of the book sold. In this way, the message that we must protect the oceans is not only passed on to the next generation, but a difference is made in the real world.

Further links

Professor Christian Voolstra is professor of genetics of adaptation in aquatic systems. He studies coral reefs, combining ecological environmental, microbial and molecular approaches. He is also the current president of the International Coral Reef Society (ICRS) and head of the Sequencing Analysis Core Facility at the University of Konstanz.

The author Alina Gries is interested in environmental issues both professionally and privately. Kira Coral is her third children's book in a themed series.

The illustrator Alina Spiekermann has already designed various children's books and works as a set designer in the film industry.

The SeaChange Indonesia coral conservation programme has been working to preserve the coral reefs in Sekotong Bay, Indonesia, since 2005.

The International Coral Reef Society (ICRS) has been supporting the scientific study of coral reefs and the dissemination of knowledge gained since 1980.

The Tara Pacific expedition, in which Christian Voolstra also took part as a researcher and scientific coordinator, is investigating the conditions for the life and survival of corals. The data obtained is open-access and anyone can use it for free.

Headerimage: Alina Spiekermann - https://www.alinaspiekermann.com/