Making a difference in the world together

Wherever people live and work, wherever there is industry and agriculture, potentially toxic chemicals can be found in the environment. The question is, how can a substance’s toxicity to humans be determined? Toxicologists at the University of Konstanz are developing animal-free testing methods to find an answer. But that is not all they are doing: Through CAAT-Europe, they are advancing international legislation on animal-free chemical safety testing at an unprecedented pace by working closely with regulatory authorities, stakeholders and industry representatives.

Not every toxicant is immediately fatal

While there are already established non-animal safety tests for the detection of acute toxicity, there are none for the identification of chemicals that cause detectable damage with a certain delay. "Existing testing methods using animals often take years and testing a single chemical can cost millions", explains Marcel Leist, professor of in vitro toxicology and biomedicine at the University of Konstanz and co-director of the CAAT-Europe.

Exposure to toxic chemicals can induce a spectrum of adverse effects in the human body. However, not all of these effects are immediately apparent. This is only the case for chemical burns, skin irritation or acute death by poisoning. Toxicological experience tells us that many chemicals only become harmful when people are exposed to them every day; others lead to harmful consequences only a long time after the exposure – causing cancer or disturbing brain development in unborn babies and children.

"In most cases, only a minimal programme of testing is carried out. In the field of industrial chemicals, for example, there is a huge lack of information on toxic effects and an urgent need for faster and more cost-efficient, reliable methods."

Marcel Leist

Unborn babies and children are particularly vulnerable

Among the most difficult consequences of chemical exposure to detect – and thus to test for – are disturbed developmental processes in children. Exposure to a chemical, for example, can have no consequences for an expectant mother, but the unborn child in the womb may be harmed. And the danger can be far from over after the baby is born: "Human babies are born at a much earlier stage of development than most other mammals. The early brain development of a child is not complete until two years after birth, not to mention the enormous structural reorganization of the brain that occurs during puberty", says Leist.

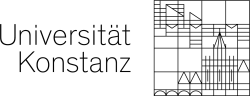

© AG LeistNeurons often form extensive networks with one another (left). Neurotoxic substances can impair or even prevent this networking, among other things (right).

The ingestion of harmful substances through breast milk or contact with chemicals during childhood also poses a high risk, especially for the developing brain. But how does the developmental neurotoxicity of chemicals manifest itself and why is it so difficult to test for? "One of the reasons for this is that neurotoxic chemicals don’t necessarily kill the cells in our nervous system. However, they do cause the neurons in the brain to connect incorrectly or incompletely, for example. In this case, the cells are there, but they don’t communicate with one another properly", explains Leist. This can result in speech and attention disorders or other cognitive defects.

Is animal testing a necessary evil?

When it comes to animal-free testing methods, the researchers at the University of Konstanz primarily use human cell cultures that are exposed to the chemical to be tested, known as the in vitro method (from the Latin: "in glass"). To find out whether a chemical causes skin irritation, for example, the results of this kind of in vitro testing can be directly transferred: researchers generate human skin in a cell culture and observe whether contact with the chemical leads to immediate damage. Naturally, this is not feasible for consequences such as cancer, organ damage or developmental disorders of the nervous system – the primary focus of Leist’s research team.

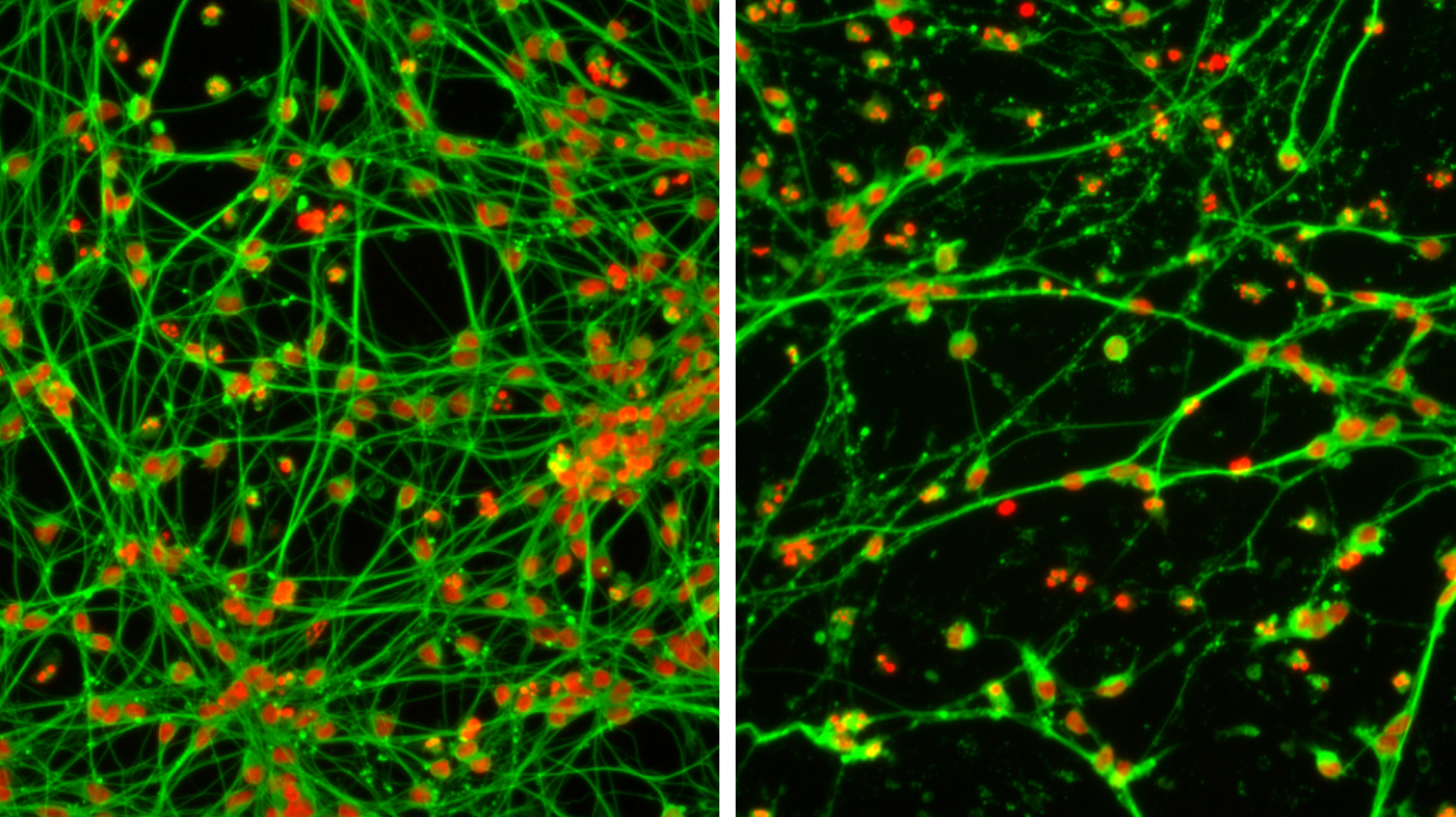

© AG LeistMicroscopic image of a neuronal network, as developed and used for testing substances in Marcel Leist’s research team.

"There are critics of in vitro testing who believe that testing complex developmental disorders in cell cultures is not possible at all, and can only be done in living organisms – in other words, animal experiments. But this is equally debatable, since laboratory rats, for example, can’t develop speech disorders. In addition, there are fundamental differences in brain development and function between animals and humans. In view of this, we are convinced that our work with human cell cultures is the more promising approach when compared to animal-based experiments, because the results are ideally more transferable and thus more relevant for us humans", states Leist.

One single test is not enough

His team from the University of Konstanz, together with international colleagues from other research facilities, has addressed the problem in a different way: They do not just use a single test to check chemicals for developmental neurotoxicity. This would not reflect all aspects of developmental disorders of the human nervous system. Instead, they have developed an entire battery of 17 different in vitro tests. All these tests are based on human stem cells and each covers different aspects of the development of the nervous system.

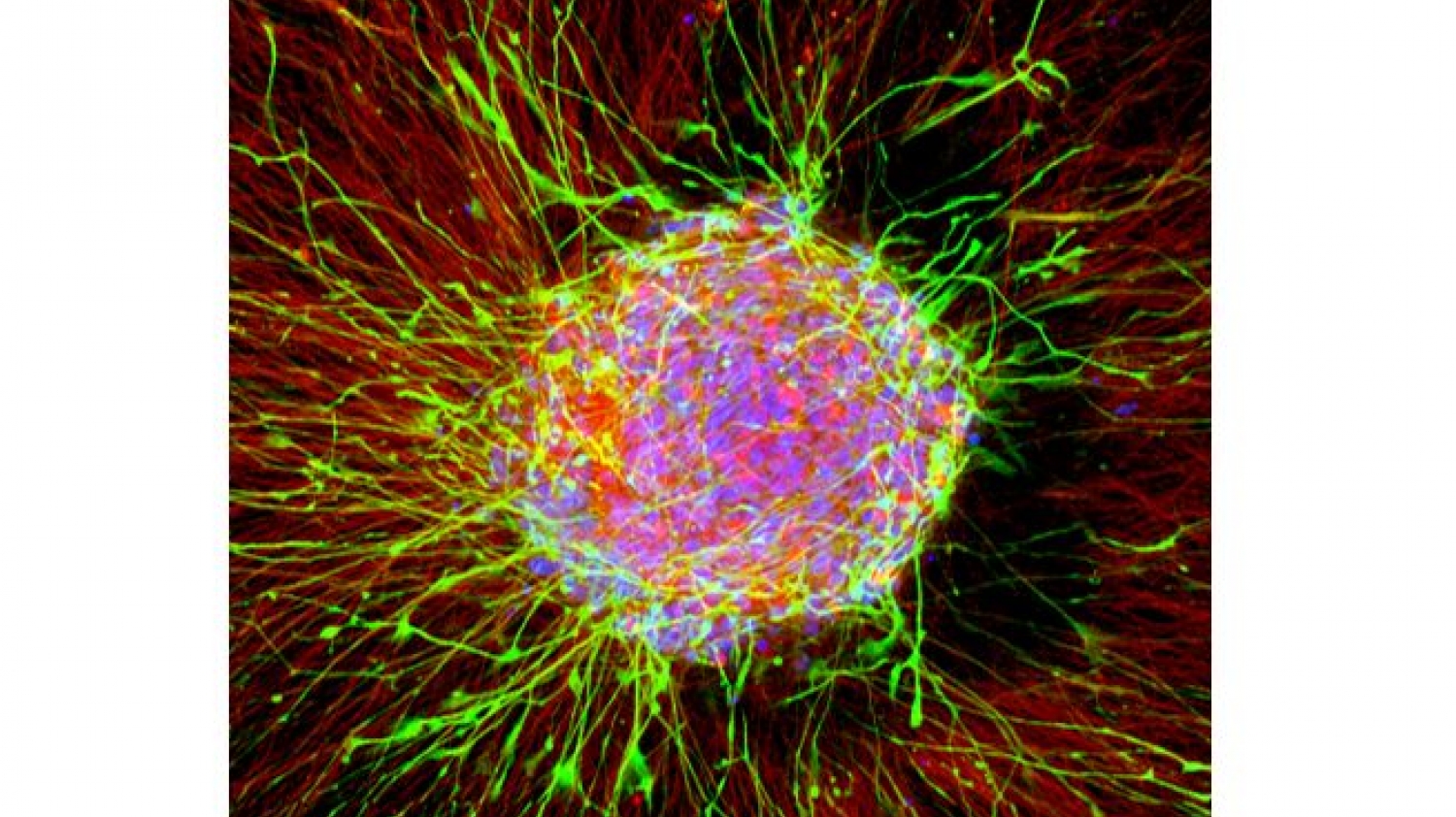

© University of KonstanzHigh-throughput microscopes are used to screen substances with the in vitro testing battery, as shown here in one of the Leist research team’s labs.

Leist and his colleagues have already presented their in-vitro testing battery to the scientific community. The findings of their study: The comprehensive testing battery was successfully implemented from a technical standpoint, and has already been used to test more than 200 chemicals. Some of the data has already been used by the authorities, and it is becoming increasingly clear that the testing sensitivity is at least on par with animal testing. The new method also provides information on neurotoxicity that was previously unavailable. The new battery of tests offers the potential to test the developmental neurotoxicity of chemicals quickly, in a cost-effective manner and with the informative value required for the regulation of hazardous substances.

The long road to widespread use

It is usually a long time from publication in a scientific journal to the global use of such an innovation. In the case of the in vitro testing battery, however, the situation is different because, in addition to its scientific expertise, the University of Konstanz has another strength: its close collaboration with all relevant stakeholders. The CAAT Europe at the University of Konstanz provides a neutral platform that brings together researchers, industry representatives and authorities, offering them the opportunity for constructive exchange before and during ongoing projects.

"Thanks to our regular exchange, for example with regulators such as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), we are able to conduct very targeted research on specific applications. After all, we keep the needs of all stakeholders involved in the regulation of chemicals in mind. At the same time, they know about the progress in our research."

Marcel Leist

This enables regulatory authorities such as the EFSA to take new research findings into account at an early stage when they are developing their strategies for chemicals risk assessments, or to contribute their own expertise during the development phase.

All key players visit Konstanz

A crucial step in the transfer of the in vitro testing battery to its practical application took place in April 2024 with the "5th International Conference on Developmental Neurotoxicity Testing (DNT5)", a professional symposium organized by the CAAT-Europe in Konstanz. In addition to researchers and representatives of major regulatory authorities and chemical companies, an international delegation from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) was also in attendance. The delegation’s aim was to be updated on the in vitro testing battery and to work on guidance for its future use in the risk assessment of chemicals.

OECD guidelines define how chemical safety is tested and reviewed in the 38 OECD member countries. But the standards set by the guidelines are also accepted outside the member countries. "Reciprocal data recognition in chemical testing is extremely important. If you want to participate in global trade, you have to agree on common standards with your trading partners, otherwise any exchange would be impossible and the global economy would collapse", explains Leist. For the in vitro testing battery, which was significantly co-developed in Konstanz, this means that as soon as the corresponding OECD guideline is available, the testing battery can and will be used worldwide for regulatory purposes.

"It usually takes many years, if not one or two decades, to reach this stage. The fact that it will probably happen much faster in our case is also due to the fact that we all – companies, research facilities, regulators and the OECD – have pulled together from the very beginning to change the existing situation for the better."

Marcel Leist

Header picture: At the DNT5 conference in April, researchers met with representatives of large chemical companies, international regulatory authorities and the OECD in Konstanz. © CAAT-Europe