Measuring brain waves to assess the effectiveness of health campaigns

Health campaigns in the mass media, such as those against drug abuse or those promoting infection prevention measures during the coronavirus pandemic, are key public health tools and help to protect the population. A recent campaign of the World Health Organization (WHO), for example, was launched in October 2024 under the motto "Redefine Alcohol". This call to action encourages people in Europe to reflect on the health effects of alcohol consumption, which, according to the WHO is currently directly responsible for one in eleven deaths in the European region.

"Unfortunately, not all health campaigns are equally effective, as our research on the effectiveness of anti-alcohol health campaigns has shown."

Harald Schupp, professor of general and biological psychology at the University of Konstanz and a member of the Konstanz Cluster of Excellence "Collective Behaviour"

Yet, how can we objectively measure the effectiveness of health-related messages, such as TV ads about addiction, in order to design evidence-based health campaigns? To develop suitable tools for this purpose, psychologists from the Konstanz Cluster of Excellence "Collective Behaviour", led by Harald Schupp and Britta Renner, are conducting studies that measure the brain activity of viewers watching real video health messages aimed at reducing risky alcohol consumption.

In laboratory experiments using advanced imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or electroencephalography (EEG), the researchers have previously demonstrated that particularly strong messages lead to an increased synchronization of viewers' brain activity. In contrast, weaker messages do not lead to the same level of synchronization in brain activity.

https://youtu.be/Hc0XpYiwJFIThe brain activity of multiple study participants is scanned using fMRI while the participants watch videos about the health risks of alcohol consumption. Each of the two brains shown in the video represents the average brain activity of one half of study participants. Areas marked in red become active at a given time, while areas in blue become less active. During particularly effective videos, the activity of both groups changed in the same way – that is, the viewers' brain activity became synchronized.

The synchronization particularly impacted regions of the brain associated with higher-order processes such as attention, emotions and personal relevance. "This shows that an important signal is being received, one that goes beyond mere seeing and hearing. We assume that what we are observing here is the audience engaging with the message of the videos", explains Martin Imhof, a researcher from Harald Schupp's team, who plays a key role in the project.

Why not just ask?

In order to measure the increased synchronization of brain activity while watching strong video messages, the research team started by compiling material from anti-alcohol health campaigns. Afterwards, they asked participants to assess whether the campaigns were 'strong' or 'weak'. "We did this repeatedly and received the same results over and over again. This means that viewers' perceptions of some campaigns as 'strong' and others as 'weak' are very robust – an important prerequisite for using them in our studies", doctoral researcher Karl-Philipp Flösch explains. This consistency allowed the researchers to compare the brain activity of study participants when watching effective videos versus ineffective ones.

If study participants reliably assessed the strength of health campaigns in surveys, what is the advantage of using neural measures such as inter-subject correlation in EEG or fMRI? "With neural measures, we can track the processes occurring in the brains of study participants as they watch these videos - something we cannot do with a survey. Neural measures thus provide us with tools for analyzing dynamic stimuli – like video or audio recordings – and, when combined with survey data, they greatly strengthen the overall analysis", Schupp adds.

Too complex for real-world application?

Even though the proof-of-concept studies by the Konstanz psychologists have delivered promising results and demonstrate that the effectiveness of video health campaigns can be measured using EEG or fMRI, there is still a problem with the methods: They are comparatively expensive, and typically have to be carried out in laboratories with electromagnetic shielding. For this reason, the videos were shown to study participants in individual sessions – and the synchronization of brain activity was calculated afterwards.

"If we insisted on adhering to ideal laboratory conditions, our tools would probably never find a real-world application."

Harald Schupp

It would simply be too complex and expensive to use the methods to develop actual health campaigns. "This is why we need to build on our proof-of-concept studies and consider how we can make these methods useful for healthcare organizations or agencies as they develop their campaigns, even without our technical resources", Schupp says.

Sometimes less is more

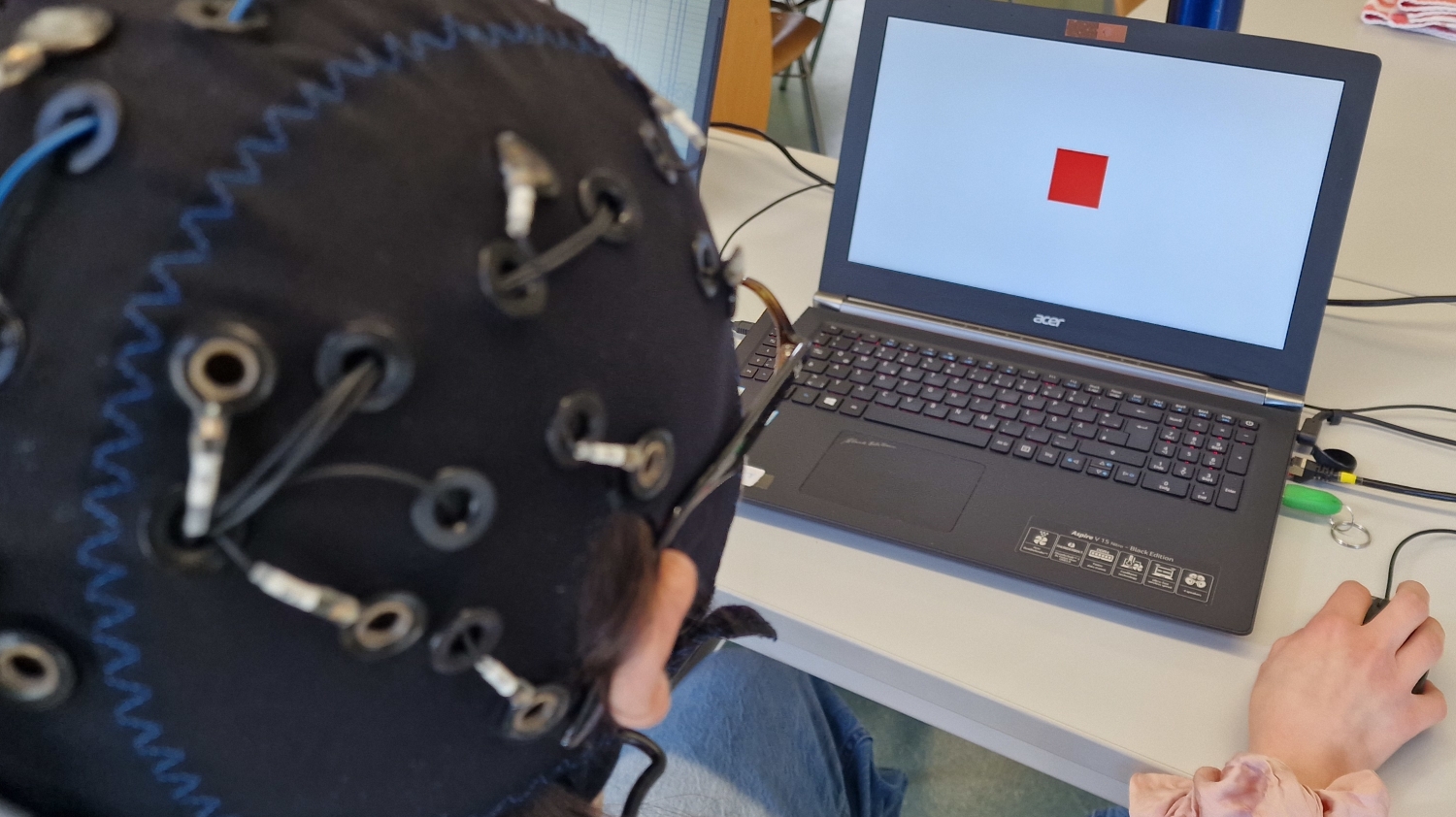

The solution is to simplify the setup. In the project's latest study, the Konstanz team took a major step forward by moving their research from the lab into a seminar room. Instead of using EEGs with 256 electrodes, they used portable, wireless EEGs with just 24 channels, which are much easier to handle. This choice enabled the researchers to carry out simultaneous measurements on groups of six people as they watched the videos together.

"This setup corresponds much better to the conditions that are likely to be found in applications outside the research setting", Schupp says. "The effectiveness of campaign materials could, for example, be evaluated by 'neural' focus groups before being rolled out." Indeed, the researchers were able to show that the synchronization of brain waves while watching particularly strong video messages against risky alcohol consumption can also be measured under these real-world conditions – using the simplified, more cost-effective technical setup. These findings move the method closer to practical application in the public health sector.

© Karl-Philipp Maria FlöschThe wireless EEG caps are also used in courses in the Department of Psychology at the University of Konstanz. Here a student tries a standard EEG experiment (oddball). © Karl-Philipp Maria Flösch

Additional research applications

"As part of the Konstanz Cluster of Excellence 'Collective Behaviour', we are interested in studying the behavioural dynamics of collectives. Being able to use the EEG method with groups of study participants therefore represents a major step forward for our other research activities", Schupp explains. In this vein, his team is currently working with other cluster researchers on a project that uses portable EEG technology to study effective group coordination at the neural level.

They measure the brain waves of people as they play together. Experimental games allow for the investigation of core psychological processes in social interaction by varying the game rules. "We hope that this approach will provide us with a mechanistic understanding of successful cooperative behaviour", Schupp says.

Header picture: Generated with AI by Gatherina | Adobe Stock, https://stock.adobe.com/de/images/brain-activity-showing-brain-waves-and...