Negotiating Europe in the Mediterranean

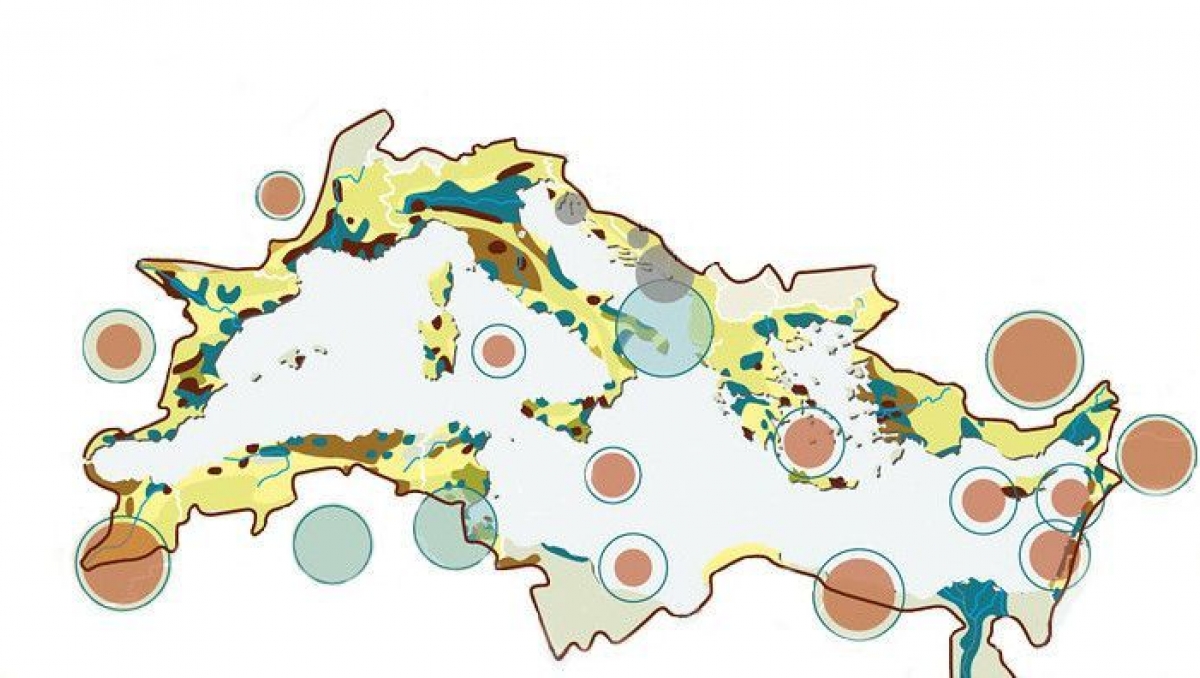

Europe is an integrative unit, and Europe is modern. These are two popular narratives of how Europe sees itself. Historian Dr Heinrich Hartmann re-assesses both of these statements by telling the history of 20th century Europe from the perspective of its rural peripheries in the Mediterranean region. He hypothesizes: "The Mediterranean successfully functioned as a region for European development. The key, however, was that the Mediterranean was not divided into a northern region that belonged to Europe and a southern region that belonged more to Africa and Asia." This holistic understanding of the Mediterranean has a long tradition that harkens back to long before the start of the 20th century.

"Even in the first few decades after World War II, the Mediterranean was still viewed as a cohesive, interconnected area, albeit one that was discussed in great part in the context of underdevelopment," says Hartmann, who is an associated member of the "Mediterranean Platform" linking cultural research about the Mediterranean region at the University of Konstanz. In fact, even in the 1970s, Turkey was considered part of this Europe. Algeria, too, was viewed as European, at least during French colonial rule. "We also want to look at the expectations involved when, for example, Turkey interacts with the European Union (EU)," the historian adds.

What does this definition of Europe look like when it is left open, when one considers who is allowed to belong to it and who belongs only partially or for a limited time? "A Europe that is not defined as the European Economic Community (EEC) or even the EU, is shaped by the semi- and cryptocolonial relationships that many countries in the Mediterranean region had. It is also shaped by organizations like the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), that arose during this period and were influenced, in key ways, by such mental maps, or subjective images of a region," says Heinrich Hartmann.

© privat"There are many overlapping regional constructs. The one that emerged as the EEC was just one of the possible options."

Dr Heinrich Hartmann

In his Heisenberg project "European knowledge networks and rural development policies in the 20th century Mediterranean", Hartmann, who researches and teaches modern and contemporary history at the University of Konstanz, pursues the topic with a knowledge and science historical approach. "We look at networks that have been established over the long-term and try to derive a complex understanding of how European borders are drawn, based on these networks." The focus is on the relationship between the modernization of agriculture and rural social forms.

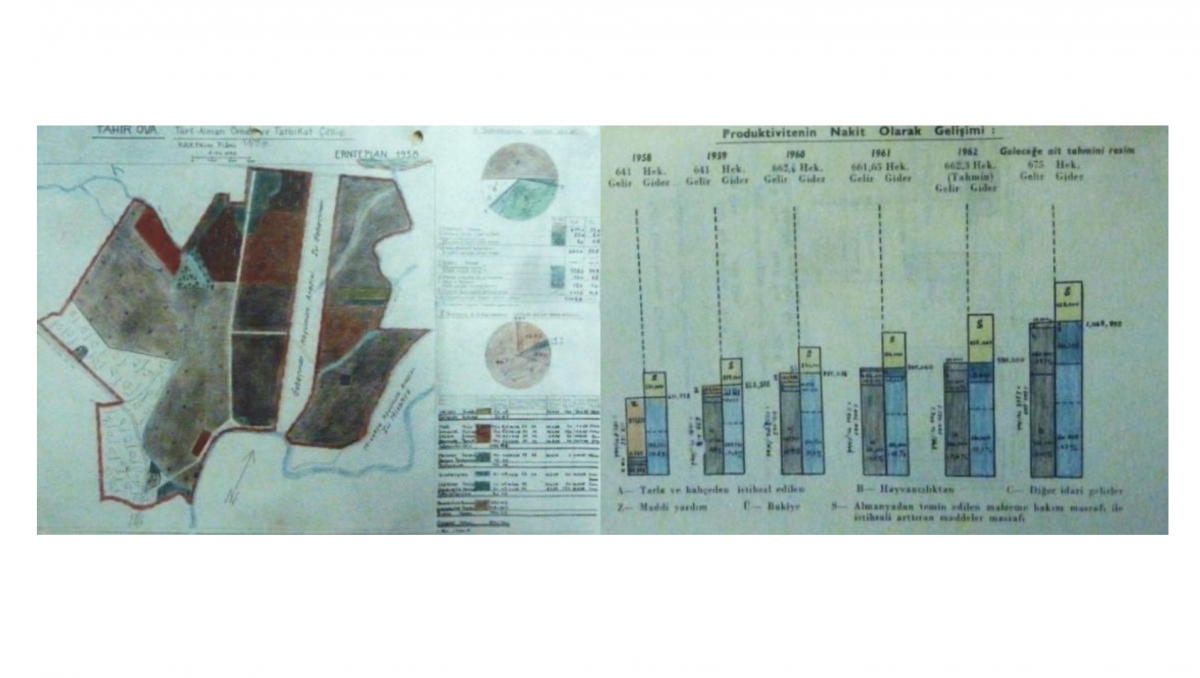

This topic builds on Hartmann's habilitation thesis, in which he examined, among other things, the work of German exile researchers in Turkey who worked in the country during the 1920s as well as during the Nazi period. "They always had a clear idea of how Turkey and the Mediterranean as a whole was to function as Europe's agricultural reserve. These people played a very important role in shaping post-war Europe." Were the concepts of underdevelopment and modernization also powerful frameworks within Europe for viewing the Mediterranean and shaping integration policy in the region?

"I also examine how the Mediterranean has been impacted by past colonial development practices."

Dr Heinrich Hartmann

In this context, he studies the career paths of people who worked in Mediterranean development policy: Germans who moved to the region during the Nazi period, French and British experts who continued to pursue their policies in the region after the colonial period, and those of them who went on to have careers in the EU administration. "I think it is particularly useful to get a feel for the longer chronology of their tradition and to see what concepts they have or where they got their influence." Contemporary witnesses, if they are available, will also be included in the project.

The researcher examines these topics in two sub-projects: Using a science historical approach, project one, "The sociology of rural modernity," will examine how the sociological descriptions of rural Mediterranean regions work, how they try to re-describe villages and shape them using specific plans – and this always in comparison to the sociological developments in Central Europe. Starting in the late 19th century, the topos of Mediterranean underdevelopment had assumed a firm place in the sociological canon.

Defining “backwardness” also became a question of which research techniques and methods were used in the process. An important part of the project will be to examine the history of sociology and anthropology in particular, as these disciplines developed their methods partially from a colonial background and now apply them to the Mediterranean.

The second sub-project, "Expertise as a cultural technique in the rural context," is concerned with the history of rural agricultural education and training in different parts of the Mediterranean. In the years after World War II, model farms emerged in Turkey, Tunisia and Spain where numerous German researchers who had gone into exile were engaged. These projects aimed to develop rural cooperatives and create new breeds of livestock in addition to the well-known new strains of wheat.

The exchange between the Mediterranean region and Western Europe as well as the renegotiation of modernization concepts must also always be taken into consideration as, in reality, imparting knowledge was not a one-way-street when experts from the north met people from the south who also had proven knowledge to offer. Thus, the project sheds new light on the history of rural societies and economic forms, which have long been viewed only from a narrow perspective of national history.

The Heisenberg project's period of investigation ends in the 1970s, when European integration policy was booming. By this time, the process of separating the southern European Mediterranean from the North African and Asian parts had concluded. This separation has impacts that are still felt today. Historian Hartmann, who lived in Turkey for a year, sees Turkey as a particularly revealing example of how "culturalist superimpositions" can polarize an economic community. Suddenly, attributions such as a fundamental difference between Islamic and Christian cultures emerged. "In the fifties, no one would have ever used this argumentation," says Heinrich Hartmann.

The Heisenberg project "European knowledge networks and rural development policies in the 20th century Mediterranean" at the University of Konstanz has been funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) since the winter semester 2021/2022. The maximum funding period is five years. It is an international project cooperation that also involves extensive internal collaboration in the Department of History and Sociology as well as the broader area of the humanities and social sciences at the University of Konstanz.

© privateIn his research, Heinrich Hartmann focuses on topics of European history with global and transnational connections. Over the past ten years, he has addressed questions about rural modernization and examined the connection between European projects of "internal colonization" and the international modernization policies of the 20th century. The rural population and their regulation plays an especially important role in this context. In his habilitation thesis, Hartmann examined the influence international experts had on Turkey's rural development policy in the 20th century. The resulting book "Eigensinnige Musterschüler" (stubborn model students) was published open access in 2020.